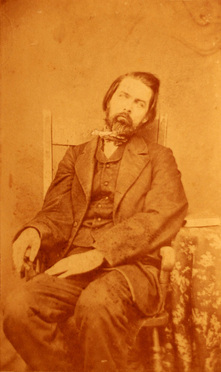

Daguerreotype Death portraits

By Andy Hagerty

While visiting a museum dedicated to the paranormal on the Gettysburg PA area, I came across something I had not really given much thought about, Death Portraits. I have been haunted ( no pun intended ) by the concept since I have come across them.

Death portraits I am talking about are often a form of early photography invented in 1839 called daguerreotype. This was the first commercially

successful form of photography. Daguerreotype process makes direct positive made in the camera on a silvered copper plate. This is a fragile print, and can be rubbed off with your fingers. There also was no negative produced , so no copies could be made. The cases provided to house Daguerreotypes have a cover lined with velvet or plush to provide a dark surface that reflects into the plate for viewing. This process takes a longer time of exposure, often 10 minutes or more, so they were not used for action shots, but needed to be used for landscapes or still scenes. This

technique remained popular up through the early 1850’s when a less expensive process called Ambrotype was developed. However it was the Tintype that sounded it’s demise in the mid 1860’s.

At the same time as this photographic process came about, there was a shift in the values of society. Karen Halttunem ( who wrote “Confidence Men and Painted Women: A Study of Middle-Class Culture in America, 1830-1870“) argues that the sentimental middle-class culture of the mid-nineteenth century included a cult of mourning. Bereavement was seen as one of the purest of deep emotions, and lengthy and emotional explorations of the joy and sadness of death were common. It was a sign of middle-class gentility, she contends, to mourn properly, and mourning became a public display for the middle class. Manuals and magazine articles explained the proper form for the bereaved and for sympathetic

friends, from dress to condolence calls.

A sizable percentage of death portraits (slightly less than half of a small sample) are not just of the dead, but include, or even focus, on their living

mourners. At least two women, in the 1840's, posed in mourning attire with daguerreotypes of their dead children, and by later in the century, this had become the norm.

Most simply, the death portrait, especially a picture of a dead child alone, was a way of remembering. What a comfort it is to possess the image of

those who are removed from our sight. We may raise an image of them in our minds but that has not the tangibility of one we can see with our bodily eyes.

–Flora A. Windeyer, in a letter to Rev. John Blomfield, November 1870

The root of the origin of photographic death portraits may be the adoption of an older tradition. Death portraits as paintings appear throughout history, and became popular in the United States in the early nineteenth century, accompanying the decline of the Puritan injunction against such "graven images" and the rise of a sentimentality of death, especially the death of children. Daguerreotypes were faster than paintings, and much cheaper, often painters would charge double if the subject was dead. This allowed the working classes to have death portraits made. Even for those with means to afford a painting death portraits were often preferred as they did a much better job at evoking the memory of the dead.

Elizabeth Barrett wrote in 1843:

I long to have a memorial of every being dear to me in the world. It is not

merely the likeness which is precious in such cases--but the association and the

sense of nearness involved in the thing...the fact of the very shadow of the

person lying there fixed forever! ...I would rather have such a memorial of one

I dearly loved, than the noblest artist's work ever produced."

The Daguerreotype death portrait had another feature that made it different from, if not better than, the painted memorial. Painted memorial portraits invariably showed a living subject, with stock symbols to indicate that the subject was dead and often idealized the person being painted. Daguerreotypes captured the physical reality of death. Karen Halttunen tells us that the mid-century middle-class "sentimental" culture privileged the moment of death itself, when the hypocrisy of a person's lifetime fell away, and the treasured last words were uttered without earthly motives. The moment of death was also seen increasingly, in the nineteenth century, as one of joy and comfort, as a release from the difficulties of this world into God's hands. A realistic daguerreotype taken just after death might show a "triumphant" entrance into God's kingdom. Death portraits could capture something of this state; in a sense, the death portrait was more accurate, in reflecting the essence of

a subject, than a portrait of the living.

An 1849 article in Godey's Lady's Book remarked on the rapidly proliferating urban daguerreotypists "busy at work in catching 'the shadow' ere

the 'substance fade. It also reflects one of the reasons that the daguerreotype was an effective memorial; imprinting, as it did, the light off a person, it seemed to include a part of his or her physical being, one that nearly captured the life of the dead. Many were struck by the fact that the daguerreotype was a shadow, a physical imprint of the departed. Some parents had death paintings of their children (made before the invention of the daguerreotype) photographed. The transferring of the image was an effort, perhaps, to capture the eerily lifelike quality of the daguerreotype, as well as its permanence.

Post mortem photography continues to this day with modern day techniques. However the Daguerreotype process created an almost surreal picture, and the conventions of the 1840’s through the Civil War created a unique form of cultural acceptance. There are hundreds of examples of this form of photography on the web. However, no matter how well scanned the photo may be, there is nothing quite like seeing one in person. Add to the experience of seeing then unexpectedly in ill lit hall of a museum in Gettysburg, and you begin to see my interest in this art form. I hope to have sparked an interest to learn more about this in my readership, and look forward to discussing your comments. We will be posting some examples of these on our face book page. Look us up, check out the photos and like us.

More pictures on our Facebook page : HERE